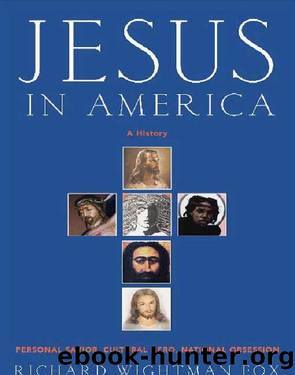

Jesus in America by Richard W. Fox

Author:Richard W. Fox

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: HarperCollins

SIX

HE TELLS ME

I AM HIS OWN

I

The end of the southern whitesâ War Between the States produced a suffering Jesus who stood for the sacrificial valor of a regional culture. Southerners could construe defeat on the battlefield of war as victory on the battlefield of spirit. Blood sacrifice brought purification, drawing the entire southern people in their devastation closer to Christ their savior. The North had mounted a mighty juggernaut, said southern Christians, but the northern soul belonged to Satanâthe same judgment voiced by many southerners from the eighteenth century to the present day. Meanwhile, the end of the northernersâ Civil War, and of the anti-slavery movement, released a broader liberalization of Christ than the one already sparked by the abolitionists. They had made him an advocate of equality and distinguished his historical consciousness as a Palestinian Jew from the unchanging truth of his basic principles. Some former abolitionists continued the egalitarian campaign during Radical Reconstructionâ keeping Jesus alive as the sword-wielding judge of John Brownâs Kansas dreamsâbut by the mid-1870s their militancy was spent. Liberal Protestants returned to the tranquil mission inaugurated by early-nineteenth-century Unitarians and stalled by the anti-slavery crusade. Jesus modeled and enacted the rule of love in society. Love ruled across the board in all human relations, public as well as private. Love transformed souls and institutions alike. Liberal Christians no longer debated whether Christ had brought peace or the sword. They returned to the effusive, progressive idealism represented by the saintly William Ellery Channing: Jesus was the Prince of Peace and the Apostle of Love.1

Like Emerson (and unlike Jefferson), mid-nineteenth-century Protestant liberals wished to break down the barrier between the natural and the supernaturalânot to naturalize the divine (the mistake they thought Theodore Parker had made), but to reveal the sacred already instilled by God in the world. Spiritual reality came in a single formâthe divine spiritâand ordinary human life pulsed with it. Likewise Christ possessed one seamless ânatureââthe spirit of loveânot the two (âtrue God and true manâ) posited by traditional theology. The liberals presented Jesus as proof that natural and supernatural spheres flowed together. They were not proposing that all reality was spiritualâthe formulation chosen by Mary Baker Eddy and her Christian Scientists in the 1870sâbut that God had already seeded the very real material world of sin with his spirit. Christ was the living symbol and embodiment of selfless love in a society given over to greed and self-aggrandizement.2

The liberalsâ blissful theorizing about the natural and the supernatural, and about the luminous Jesus who reconciled all good things to himself, comprised one central pillar of a much broader nineteenth-century liberal faith in reason, science, and morality as the motors of American progress. Most liberal Protestants gladly embraced scientific knowledge, including the scholarship of post- Civil War biblical criticism. Nearly all Americans, for that matter, reveled in what they called âscience.â They rejected only a skeptical science that declared outright war on religion or religious beliefâand that kind of anti-clerical science was rare in mid-nineteenth-century America.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(9006)

Tools of Titans by Timothy Ferriss(8403)

Giovanni's Room by James Baldwin(7354)

The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(7137)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6800)

The Way of Zen by Alan W. Watts(6621)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5790)

Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking by M. Neil Browne & Stuart M. Keeley(5779)

The Six Wives Of Henry VIII (WOMEN IN HISTORY) by Fraser Antonia(5519)

Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil DeGrasse Tyson(5196)

Housekeeping by Marilynne Robinson(4455)

12 Rules for Life by Jordan B. Peterson(4312)

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles(4279)

Double Down (Diary of a Wimpy Kid Book 11) by Jeff Kinney(4278)

The Ethical Slut by Janet W. Hardy(4262)

Skin in the Game by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4257)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4133)

Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life by Nassim Nicholas Taleb(4012)

Walking by Henry David Thoreau(3969)